Content from Day 1

Last updated on 2025-01-07 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- [insert questions about R basics]

Objectives

- [insert objectives of day 1]

Lecture Recording and Files

Below is the rendered and completed version of Day 1’s R Markdown file. Begin with the empty version here. You will also need to download the following

All Introduction to R (2024) course materials are available here.

Introduction to R

We will be learning the programming language of R using the RStudio IDE interface.

R studio allows for working in many different file types. For this

workshop, we will be using R Markdown files. They have a

.Rmd file extension. In this current file, you will find

two types of areas. This current area is for markdown text.

Code will not be executed here and you can use markdown formatting such

as bold and italics.

I encourage you to take advantage of this space to take notes throughout the lessons, feel free to add/edit any of the text in this document! Markdown text will not affect how the code is run.

The second area will is call code chucks such as the one immediately below this. Code chunks always start with three ``` followed by the name of the language you are using in the chunk. You can press the green play button in the top right corner within each chunk or the run the cell.

Edit

R

x <- 123

x

OUTPUT

[1] 123R

y = 2

y

OUTPUT

[1] 2The put arrow is used to assign value in objects. While a single equal sign can work as well, it is not good coding practice for R and should be saved for specifying parameters within functions (we’ll get back to this)

Some common keyboard shortcuts that may be useful:

cntl/cmd + alt + i - insert a new code cell (or press the green c with a + in the console toolbar) cntl/cmd + enter - run only the line your cursor is on cntl/cmd + shift + enter - run all lines in the cell (or press the green play button)

Feel free to try editing the code above, perhaps by multiply the value of x by 2.

Within code cells, you can also add comments by starting a line with

a hashtag # to indicate lines you do not want to run. I

will use this often for guidance or instructions, this is another great

way to take notes throughout the workshop

Follow the instructions to write your first script!

math can only be done on numerics

R

# Save the value of 12 to an object called "dozen"

dozen <- 12

#dozen

# Use this object to calculate how many eggs are in 14 dozen eggs

dozen*14

OUTPUT

[1] 168General syntax

Multiple values can be stored into an object using the function

c() for combine or concatenate

R

prime <- c(1, 3, 5, 7)

prime

OUTPUT

[1] 1 3 5 7Functions act on objects and can have additional parameters within the round brackets to specify how the command is carried out

R

prime_mean <- mean(prime)

prime_mean

OUTPUT

[1] 4R

#mean() NOTE: BUG IN COMPLETED CODE, MEAN() REQUIRES PARAMETERS

All functions have default parameters that you can access using the

help panel (same area as the “Files” and “Plots” panel) or using a

? before the function name

R

?mean

Getting started with data

Data can be created de novo from within R or read in from an external object. Either way, there are a few broad categories of data types that you will encounter:

-

Vectors - 1 dimensional, for example the string of numbers

in our

primeobject - Data frames - 2 dimensional, for example a table with rows of patients and columns for clinical characteristics

- Lists - complex 1 dimensional, can store data of different types within a single object

Vectors can only hold one type of data within a single object

R

# Numeric

first5 <- c(1:5)

first5

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4 5R

# Character

fruits <- c('orange', "apple", "banana", "grapefruit", "starfruit")

fruits

OUTPUT

[1] "orange" "apple" "banana" "grapefruit" "starfruit" R

# Logical

evaluate <- 64 == 46

evaluate

OUTPUT

[1] FALSE1 dimensional vectors can be used by themselves or used as the foundation for creating data frames

R

firstDF <- data.frame(first5, fruits)

firstDF

OUTPUT

first5 fruits

1 1 orange

2 2 apple

3 3 banana

4 4 grapefruit

5 5 starfruitR

class(firstDF)

OUTPUT

[1] "data.frame"R

colnames(firstDF)

OUTPUT

[1] "first5" "fruits"R

rownames(firstDF)

OUTPUT

[1] "1" "2" "3" "4" "5"R

dim(firstDF) # ALWAYS rows then columns

OUTPUT

[1] 5 2Dataframes are the most common way of storing information. One of

their major strengths is that you can access piece of information

independently. Square brackets [] are used to access data

within an object, always in the format of [rows,columns].

If you want to grab a specific row but all the columns of that row, you

can leave the column specifier blank - but you always need the comma

there regardless.

R

prime[2]

OUTPUT

[1] 3R

firstDF [2, 4] # [rows,col]

OUTPUT

NULLImporting data

Rather than entering you data manually, you are more likely to read in data from an external source such as an output file from a machine or data stored in an excel table. R is pretty flexible with the files that it can accept, but there are differences to how it is read in.

The recommended format is a .csv file. This stands for

“comma separated values”. This means columns are separated by commas and

rows are separated by hard enters.

In this module, we will be working with an dataset measuring categorical and integral characteristics of abalone gathered in Australia

Source:

Data comes from an original (non-machine-learning) study: Warwick J Nash, Tracy L Sellers, Simon R Talbot, Andrew J Cawthorn and Wes B Ford (1994) “The Population Biology of Abalone (Haliotis species) in Tasmania. I. Blacklip Abalone (H. rubra) from the North Coast and Islands of Bass Strait”, Sea Fisheries Division, Technical Report No. 48 (ISSN 1034-3288) https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/abalone

Data Set Information:

Predicting the age of abalone from physical measurements. The age of abalone is determined by cutting the shell through the cone, staining it, and counting the number of rings through a microscope – a boring and time-consuming task. Other measurements, which are easier to obtain, are used to predict the age. Further information, such as weather patterns and location (hence food availability) may be required to solve the problem.

Attribute Information:

Given is the attribute name, attribute type, the measurement unit and a brief description. The number of rings is the value to predict: either as a continuous value or as a classification problem.

Name / Data Type / Measurement Unit / Description

- Sex / nominal / – / M, F, and I (infant)

- Length / continuous / mm / Longest shell measurement

- Diameter / continuous / mm / perpendicular to length

- Height / continuous / mm / with meat in shell

- Whole weight / continuous / grams / whole abalone

- Shucked weight / continuous / grams / weight of meat

- Viscera weight / continuous / grams / gut weight (after bleeding)

- Shell weight / continuous / grams / after being dried

- Rings / integer / – / +1.5 gives the age in years

As this is a csv file, we will be using the aptly named function “read.csv()” to import the file into R. Make sure your abalone.csv file is in the same directory/folder as your .Rmd file. The first parameter the read.csv() function requires is the path to the file. This will just be the file name since they are both within the same folder.

If the dataset your working with is not in the same folder, you can

modify the path to navigate through your directories to locate the file

or use the Import Dataset button.

Notice when we open the abalone dataset that the first row holds the column names rather than the first set of observations. We will need to let R know that there is a header in the parameters of the read.csv() function.

R

#abalone <- read.csv("anotherfolder//abalone.csv", header = TRUE)

#abalone <- read.csv("C:/Users/Frances/Downloads/BioinformaticsWorkshop_INR_June2024-20240611T023701Z-001/BioinformaticsWorkshop_INR_June2024/abalone.csv")

abalone <- read.csv("data/abalone.csv", header = TRUE)

#abalone - commented out since it is a massive file

It is almost never useful to print out the whole table because humans are not good at inspecting numbers. Built in summary statistics are helpful for us to get an overview of the data.

R

str(abalone)

OUTPUT

'data.frame': 4177 obs. of 9 variables:

$ Sex : chr "M" "M" "F" "M" ...

$ Length : num 0.455 0.35 0.53 0.44 0.33 0.425 0.53 0.545 0.475 0.55 ...

$ Diameter : num 0.365 0.265 0.42 0.365 0.255 0.3 0.415 0.425 0.37 0.44 ...

$ Height : num 0.095 0.09 0.135 0.125 0.08 0.095 0.15 0.125 0.125 0.15 ...

$ Whole.weight : num 0.514 0.226 0.677 0.516 0.205 ...

$ Shucked.weight: num 0.2245 0.0995 0.2565 0.2155 0.0895 ...

$ Viscera.weight: num 0.101 0.0485 0.1415 0.114 0.0395 ...

$ Shell.weight : num 0.15 0.07 0.21 0.155 0.055 0.12 0.33 0.26 0.165 0.32 ...

$ Rings : int 15 7 9 10 7 8 20 16 9 19 ...R

summary(abalone)

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height

Length:4177 Min. :0.075 Min. :0.0550 Min. :0.0000

Class :character 1st Qu.:0.450 1st Qu.:0.3500 1st Qu.:0.1150

Mode :character Median :0.545 Median :0.4250 Median :0.1400

Mean :0.524 Mean :0.4079 Mean :0.1395

3rd Qu.:0.615 3rd Qu.:0.4800 3rd Qu.:0.1650

Max. :0.815 Max. :0.6500 Max. :1.1300

Whole.weight Shucked.weight Viscera.weight Shell.weight

Min. :0.0020 Min. :0.0010 Min. :0.0005 Min. :0.0015

1st Qu.:0.4415 1st Qu.:0.1860 1st Qu.:0.0935 1st Qu.:0.1300

Median :0.7995 Median :0.3360 Median :0.1710 Median :0.2340

Mean :0.8287 Mean :0.3594 Mean :0.1806 Mean :0.2388

3rd Qu.:1.1530 3rd Qu.:0.5020 3rd Qu.:0.2530 3rd Qu.:0.3290

Max. :2.8255 Max. :1.4880 Max. :0.7600 Max. :1.0050

Rings

Min. : 1.000

1st Qu.: 8.000

Median : 9.000

Mean : 9.934

3rd Qu.:11.000

Max. :29.000 Notice for the sex of the observations, the summary is returning that there are characters in this column but not much else. Let’s take a look at the data in this column closer

The sting $ operator is used to access a column within a

dataframe.

R

head(abalone$Sex, n=20) # object$columnName

OUTPUT

[1] "M" "M" "F" "M" "I" "I" "F" "F" "M" "F" "F" "M" "M" "F" "F" "M" "I" "F" "M"

[20] "M"R

class(abalone$Sex)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"R

abalone$Sex <- as.character(abalone$Sex)

As a column of character values, the relationship between the observations being recorded as “M”, “F’, or”I” are not being recognized. We will need convert this column to factor.

R

head(as.factor(abalone$Sex))

OUTPUT

[1] M M F M I I

Levels: F I MR

summary(as.factor(abalone$Sex))

OUTPUT

F I M

1307 1342 1528 Now that we understand factors, let’s overwrite the column in the original dataset. Remember, there is no undo button in programming. Double check your work before you overwrite objects

R

abalone$Sex <- as.factor(abalone$Sex)

head(abalone)

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height Whole.weight Shucked.weight Viscera.weight

1 M 0.455 0.365 0.095 0.5140 0.2245 0.1010

2 M 0.350 0.265 0.090 0.2255 0.0995 0.0485

3 F 0.530 0.420 0.135 0.6770 0.2565 0.1415

4 M 0.440 0.365 0.125 0.5160 0.2155 0.1140

5 I 0.330 0.255 0.080 0.2050 0.0895 0.0395

6 I 0.425 0.300 0.095 0.3515 0.1410 0.0775

Shell.weight Rings

1 0.150 15

2 0.070 7

3 0.210 9

4 0.155 10

5 0.055 7

6 0.120 8Exercise 1 (10 mins)

Explore the abalone dataset.

A. Determine the sex of abalone (col) number 65, 85, and 99 (rows) B. Out of these three abalone, determine which of the three oysters is largest diameter C. Use the “mean()” function to determine the mean abalone diameter overall (not just the three)

Remember: error messages are normal and part of the troubleshooting process. This is R’s way of communicating where to double check - not an indication of your ability to code! You’re doing great!

Take down your green stickies at the start of this activity and put them up when you’re done and ready to re-group!

R

# Hints to get you started:

# Square brackets are used to access position: object[row,columns]

# The function c() for combine or concatenate is needed when there are multiple inputs

# Numeric values should not be enclosed in quotations, but character values require quotations.

abalone$Diameter[c(65, 85, 99)]

OUTPUT

[1] 0.40 0.45 0.37R

colnames(abalone)

OUTPUT

[1] "Sex" "Length" "Diameter" "Height"

[5] "Whole.weight" "Shucked.weight" "Viscera.weight" "Shell.weight"

[9] "Rings" R

abalone[c(65, 85, 99), 3] #"Diameter"]

OUTPUT

[1] 0.40 0.45 0.37R

abalone_diameter <- abalone[c(65, 85, 99), 3]

abalone_diameter

OUTPUT

[1] 0.40 0.45 0.37R

mean(abalone$Diameter)

OUTPUT

[1] 0.4078813Good job writing your first investigative pieces of code! Woo hoo!

Revising the R environment

Let’s take a moment to revisit the Rstudio interface and the environment panel.

We’ve worked with a few objects at this point. The environment panel can give us an overview of the objects in the environment and allow us to preview dataframes.

If you would like to remove any objects, perhaps you made two objects

that are very close in spelling and want to remove the incorrect object,

you can use the function rm() for remove.

Again, this is an irreversible action - double check your work. If you’ve documented your code properly, you can always re-read in the object in case you mistakenly deleted anything you wanted to keep.

R

#ABalone <- "blank"

#rm(ABalone)

The “object not found” error is a common one. In case you get this, you can refer to this environment tab to double check if it exists. Some common reasons this error message is triggered include:

- Typo mistakes (ex. firstDf vs firstDF)

- Empty environment (ex. object need to be created everytime you open the document. If you save and close RStudio, the text in the .Rmd file will be preserved but not the virtual objects in the environment.)

As an overview of our environment, we can also use the

sessionInfo() command. This is a good practice to have at

the end of your code to document which packages you used and what

version they were.

R

sessionInfo()

OUTPUT

R version 4.4.2 (2024-10-31)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Running under: Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/blas/libblas.so.3.10.0

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/lapack/liblapack.so.3.10.0

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=C.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C LC_TIME=C.UTF-8

[4] LC_COLLATE=C.UTF-8 LC_MONETARY=C.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=C.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=C.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C LC_ADDRESS=C

[10] LC_TELEPHONE=C LC_MEASUREMENT=C.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

time zone: UTC

tzcode source: system (glibc)

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] compiler_4.4.2 tools_4.4.2 yaml_2.3.10 knitr_1.48

[5] xfun_0.46 renv_1.0.11 evaluate_0.24.0Notice that we have some base packages active even though we did not explicitly call for them.

Installing packages from CRAN

Before we move on to a break, let’s revisit functions and packages. Functions are the commands we use to act on objects. As an open source software, anyone can develop new functions and package them into … packages to share with the community! Virtually anything you want to do - so does someone else!

Referring back to my introduction presentation, R includes many

pre-installed functions like c() and summary()

that we’ve been using. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. We’ll be

exploring a package called tidyverse developed to wrangle and reshape

data. We will need to install this package only the first time we’re

using it, similar to how we need to download a new app to our phones or

computers before using it. Every time we want to use it, we still need

to open it.

Most general use packages are hosted on the CRAN network. Another

package repository you will encounter specifically for biological

applications is called Bioconductor (we won’t be using this for now). To

download and install a package from CRAN, we will use another aptly

named packaged called install.packages()

Since R has not encountered the package before, we will need to use brackets around the name of the package we want to install

R

#install.packages("tidyverse")

library(tidyverse)

OUTPUT

── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

✔ ggplot2 3.5.1 ✔ tibble 3.2.1

✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

✔ purrr 1.0.2

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorsOnce you have it installed, you can “open” them. You need to activate the library every new session of R.

You will likely see some warning messages – warnings are not error messages. - Error messages mean that R could not do what you asked it to and tries to explain the problem - Warning messages mean that R did what it think you wanted to do but wants to caution you to double check some parameters

In this case, the “Attaching packages” indicates the tidyverse

package in opening other accompanying packages as well that it needs to

function. “Conflicts” indicate that there are separate packages with

functions of the same name and which one takes priority. To access a

function from a specific package, you can use the syntax

package::function()

R

library(tidyverse)

Data Wrangling

Most of the raw data we work with starts off as what the computer considers messy. Perhaps there are some observations with incomplete data (columns are missing data) or there are multiple observations stored in each row (imagine a table with countries in the rows and a column for life expectancy in 1990 in one column and life expectancy in 2010 in the adjacent column).

Data wrangling is the process of data cleaning and reshaping the raw data into a more usable form. This can be a lengthy process, and can often not feel as rewarding as generating statistical analysis or beautiful plots. But this is the foundation of your analysis so it is worth the investment! Data wrangling can also be an intimidating task because there is no straight forward formula to follow. How you clean up your data depends on what you’re starting with, what research question you are trying to address, and which packages you’re using in your analysis.

In this section, we are going to get comfortable subseting the data and re-shaping dataframes. We’ll start by reminding ourselves how our dataset looks:

R

head(abalone)

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height Whole.weight Shucked.weight Viscera.weight

1 M 0.455 0.365 0.095 0.5140 0.2245 0.1010

2 M 0.350 0.265 0.090 0.2255 0.0995 0.0485

3 F 0.530 0.420 0.135 0.6770 0.2565 0.1415

4 M 0.440 0.365 0.125 0.5160 0.2155 0.1140

5 I 0.330 0.255 0.080 0.2050 0.0895 0.0395

6 I 0.425 0.300 0.095 0.3515 0.1410 0.0775

Shell.weight Rings

1 0.150 15

2 0.070 7

3 0.210 9

4 0.155 10

5 0.055 7

6 0.120 8R

abalone$Sex <- as.factor(abalone$Sex)

If we wanted to take a look at the summary statistics independently for infant vs mature, we can create multiple objects by subseting the original one.

Remember for square brackets are indexing an object. For data frames, it is expecting two specifications separated by a comma, which rows followed by which columns.

R

abalone_infants <- abalone[abalone$Sex == "I", ] #object[rows, col]

summary(abalone_infants)

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height Whole.weight

F: 0 Min. :0.0750 Min. :0.0550 Min. :0.000 Min. :0.0020

I:1342 1st Qu.:0.3600 1st Qu.:0.2700 1st Qu.:0.085 1st Qu.:0.2055

M: 0 Median :0.4350 Median :0.3350 Median :0.110 Median :0.3840

Mean :0.4277 Mean :0.3265 Mean :0.108 Mean :0.4314

3rd Qu.:0.5100 3rd Qu.:0.3900 3rd Qu.:0.130 3rd Qu.:0.5994

Max. :0.7250 Max. :0.5500 Max. :0.220 Max. :2.0495

Shucked.weight Viscera.weight Shell.weight Rings

Min. :0.0010 Min. :0.00050 Min. :0.00150 Min. : 1.00

1st Qu.:0.0900 1st Qu.:0.04250 1st Qu.:0.06413 1st Qu.: 6.00

Median :0.1698 Median :0.08050 Median :0.11300 Median : 8.00

Mean :0.1910 Mean :0.09201 Mean :0.12818 Mean : 7.89

3rd Qu.:0.2704 3rd Qu.:0.13000 3rd Qu.:0.17850 3rd Qu.: 9.00

Max. :0.7735 Max. :0.44050 Max. :0.65500 Max. :21.00 We can select for multiple values as well.

R

#abalone_infants <- abalone[abalone$Sex == "I", ]

abalone_mature <- abalone[abalone$Sex == c("F", "M"), ]

WARNING

Warning in `==.default`(abalone$Sex, c("F", "M")): longer object length is not

a multiple of shorter object lengthWARNING

Warning in is.na(e1) | is.na(e2): longer object length is not a multiple of

shorter object lengthR

summary(abalone_mature)

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height Whole.weight

F:659 Min. :0.1550 Min. :0.1150 Min. :0.0150 Min. :0.0230

I: 0 1st Qu.:0.5150 1st Qu.:0.4000 1st Qu.:0.1350 1st Qu.:0.7127

M:763 Median :0.5800 Median :0.4600 Median :0.1550 Median :1.0100

Mean :0.5699 Mean :0.4469 Mean :0.1543 Mean :1.0220

3rd Qu.:0.6350 3rd Qu.:0.5000 3rd Qu.:0.1750 3rd Qu.:1.2971

Max. :0.8150 Max. :0.6500 Max. :0.5150 Max. :2.8255

Shucked.weight Viscera.weight Shell.weight Rings

Min. :0.0085 Min. :0.0050 Min. :0.0050 Min. : 3.00

1st Qu.:0.2941 1st Qu.:0.1535 1st Qu.:0.2050 1st Qu.: 9.00

Median :0.4300 Median :0.2150 Median :0.2870 Median :10.00

Mean :0.4430 Mean :0.2232 Mean :0.2928 Mean :10.88

3rd Qu.:0.5725 3rd Qu.:0.2874 3rd Qu.:0.3699 3rd Qu.:12.00

Max. :1.3485 Max. :0.7600 Max. :0.8970 Max. :29.00 Exercise

Create a new object called abalone_small with only

abalone with Whole.weight less than 1. Include only the

columns Sex, Length, Diameter,

and Whole.weight.

You can do this in one line or multiple lines, whichever you are most

comfortable with! Take your time and check your work along the way using

the summary() function.

R

# object[rows, col]

colnames(abalone)

OUTPUT

[1] "Sex" "Length" "Diameter" "Height"

[5] "Whole.weight" "Shucked.weight" "Viscera.weight" "Shell.weight"

[9] "Rings" R

abalone_small <- abalone[abalone$`Whole.weight` <1, c(1, 2, 3, 5)]

abalone_small <- abalone[abalone$Whole.weight <1, c("Sex", "Length", "Diameter", "Whole.weight")]

summary(abalone_small)

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Whole.weight

F: 614 Min. :0.0750 Min. :0.055 Min. :0.0020

I:1293 1st Qu.:0.4000 1st Qu.:0.305 1st Qu.:0.3040

M: 798 Median :0.4800 Median :0.375 Median :0.5420

Mean :0.4613 Mean :0.356 Mean :0.5358

3rd Qu.:0.5400 3rd Qu.:0.420 3rd Qu.:0.7800

Max. :0.6350 Max. :0.510 Max. :0.9995 Adding new columns of data

New columns can also be created if you wanted to add more information to the dataset

R

abalone$maturity <- "mature"

table(abalone$maturity)

OUTPUT

mature

4177 R

abalone[abalone$Sex == "I", "maturity"] <- "infant"

table(abalone$maturity)

OUTPUT

infant mature

1342 2835 R

table(abalone$maturity, abalone$Sex)

OUTPUT

F I M

infant 0 1342 0

mature 1307 0 1528Remember that operations can be done on whole columns as well!!

R

abalone$Percent.weight <- abalone$Shucked.weight/abalone$Shell.weight

head(abalone)

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height Whole.weight Shucked.weight Viscera.weight

1 M 0.455 0.365 0.095 0.5140 0.2245 0.1010

2 M 0.350 0.265 0.090 0.2255 0.0995 0.0485

3 F 0.530 0.420 0.135 0.6770 0.2565 0.1415

4 M 0.440 0.365 0.125 0.5160 0.2155 0.1140

5 I 0.330 0.255 0.080 0.2050 0.0895 0.0395

6 I 0.425 0.300 0.095 0.3515 0.1410 0.0775

Shell.weight Rings maturity Percent.weight

1 0.150 15 mature 1.496667

2 0.070 7 mature 1.421429

3 0.210 9 mature 1.221429

4 0.155 10 mature 1.390323

5 0.055 7 infant 1.627273

6 0.120 8 infant 1.175000Tidyverse

Tidyverse is a collection of packages, or an “umbrella-package” the installs tidyr, dplyr, ggplot2, and several other related packages for tidying up your data.

Keep in mind that tidyverse creates their own rules for R and their functions work well with their own functions, but may not translate to work well with other packages build by different developers. For example, the core developer strongly believes that rownames are not useful and all the information should be stored in columns within the table so converting your data frame to their object variation called tibbles will automatically remove rownames without warnings.

Rather than using square brackets to subset columns, we can select the rows that we want

R

#select(abalone, Diameter, Length, Whole.weight) #Tidyverse selecting columns - COMMENTED OUT DUE TO SIZE ON WINDOW

#abalone$Diameter #base R - COMMENTED OUT DUE TO SIZE ON WINDOW

select can also be used to exclude specific columns

R

#select(abalone, -Length, -Diameter) - COMMENTED OUT DUE TO SIZE ON WINDOW

Select only works on columns. We can use a similar function to filter for the rows that we want

R

# Filter indexes rows

#filter(abalone, Sex == "I") # abalone[abalone$Sex == "I", ] - COMMENTED OUT DUE TO SIZE ON WINDOW

summary(filter(abalone, Sex == c("I")))

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height Whole.weight

F: 0 Min. :0.0750 Min. :0.0550 Min. :0.000 Min. :0.0020

I:1342 1st Qu.:0.3600 1st Qu.:0.2700 1st Qu.:0.085 1st Qu.:0.2055

M: 0 Median :0.4350 Median :0.3350 Median :0.110 Median :0.3840

Mean :0.4277 Mean :0.3265 Mean :0.108 Mean :0.4314

3rd Qu.:0.5100 3rd Qu.:0.3900 3rd Qu.:0.130 3rd Qu.:0.5994

Max. :0.7250 Max. :0.5500 Max. :0.220 Max. :2.0495

Shucked.weight Viscera.weight Shell.weight Rings

Min. :0.0010 Min. :0.00050 Min. :0.00150 Min. : 1.00

1st Qu.:0.0900 1st Qu.:0.04250 1st Qu.:0.06413 1st Qu.: 6.00

Median :0.1698 Median :0.08050 Median :0.11300 Median : 8.00

Mean :0.1910 Mean :0.09201 Mean :0.12818 Mean : 7.89

3rd Qu.:0.2704 3rd Qu.:0.13000 3rd Qu.:0.17850 3rd Qu.: 9.00

Max. :0.7735 Max. :0.44050 Max. :0.65500 Max. :21.00

maturity Percent.weight

Length:1342 Min. : 0.1641

Class :character 1st Qu.: 1.2585

Mode :character Median : 1.4563

Mean : 1.5092

3rd Qu.: 1.6752

Max. :15.7143 Functions within the tidyverse universe do not require quotations around column names - this is unique to tidyverse packages and does not translate to other applications!

Another unique aspect of tidyverse is that their commands can be

chained together using the pipe %>%. This cumbersome

chain of characters can be inserted with the shortcut cnt/cmd + shift +

M.

Let’s recreate the same object of abalone_small first with intermediate objects

Reminder of the object requirements: - Whole.weight under 1 - Columns Length, Diameter, and Whole.weight

R

abalone_sub1 <- filter(abalone, Whole.weight < 1)

abalone_sub2 <- select(abalone_sub1, Length, Diameter, Whole.weight)

summary(abalone_sub2)

OUTPUT

Length Diameter Whole.weight

Min. :0.0750 Min. :0.055 Min. :0.0020

1st Qu.:0.4000 1st Qu.:0.305 1st Qu.:0.3040

Median :0.4800 Median :0.375 Median :0.5420

Mean :0.4613 Mean :0.356 Mean :0.5358

3rd Qu.:0.5400 3rd Qu.:0.420 3rd Qu.:0.7800

Max. :0.6350 Max. :0.510 Max. :0.9995 Now we’re going to combine this all together into one call

R

abalone_sub3 <- abalone %>%

filter(Whole.weight < 1) %>%

select(Length, Diameter, Whole.weight)

head(abalone_sub3)

OUTPUT

Length Diameter Whole.weight

1 0.455 0.365 0.5140

2 0.350 0.265 0.2255

3 0.530 0.420 0.6770

4 0.440 0.365 0.5160

5 0.330 0.255 0.2050

6 0.425 0.300 0.3515R

summary(abalone_sub3)

OUTPUT

Length Diameter Whole.weight

Min. :0.0750 Min. :0.055 Min. :0.0020

1st Qu.:0.4000 1st Qu.:0.305 1st Qu.:0.3040

Median :0.4800 Median :0.375 Median :0.5420

Mean :0.4613 Mean :0.356 Mean :0.5358

3rd Qu.:0.5400 3rd Qu.:0.420 3rd Qu.:0.7800

Max. :0.6350 Max. :0.510 Max. :0.9995 The functions are the same but since we are piping the results of the previous line to the next command, you do not need to (and should not) specify the object as the first argument in the function.

group_by() and summarize() functions can be

used to get summary statistics without the need to create intermediate

objects

R

abalone_sub3 <- abalone %>%

filter(Whole.weight < 1) %>%

select(Length, Diameter, Whole.weight, Sex) %>%

group_by(Sex) %>%

summarize(my_own_function = median(Whole.weight))

abalone_sub3

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 2

Sex my_own_function

<fct> <dbl>

1 F 0.707

2 I 0.370

3 M 0.694Exercise

Using the base abalone object and tidyverse functions, investigate

whether the mean length of male or females (group_by) are longer of

abalone with a Shucked.weight greater than 0.3 AND a

Shell.weight less than 0.3 (filtering rows) .

Include a checkpoint in your summarize call to make sure your filter worked.

R

abalone %>%

filter(Shucked.weight > 0.3, Shell.weight < 0.3) %>%

group_by(Sex) %>%

summarize(mean_Length = mean(Length),

min_Shucked = min(Shucked.weight))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 3

Sex mean_Length min_Shucked

<fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 F 0.569 0.300

2 I 0.547 0.300

3 M 0.567 0.301Lastly, we can also use mutate() to add a new column of

information based on existing data.

R

abalone %>%

mutate(Whole.weight.oz = Whole.weight*0.035) %>%

head()

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height Whole.weight Shucked.weight Viscera.weight

1 M 0.455 0.365 0.095 0.5140 0.2245 0.1010

2 M 0.350 0.265 0.090 0.2255 0.0995 0.0485

3 F 0.530 0.420 0.135 0.6770 0.2565 0.1415

4 M 0.440 0.365 0.125 0.5160 0.2155 0.1140

5 I 0.330 0.255 0.080 0.2050 0.0895 0.0395

6 I 0.425 0.300 0.095 0.3515 0.1410 0.0775

Shell.weight Rings maturity Percent.weight Whole.weight.oz

1 0.150 15 mature 1.496667 0.0179900

2 0.070 7 mature 1.421429 0.0078925

3 0.210 9 mature 1.221429 0.0236950

4 0.155 10 mature 1.390323 0.0180600

5 0.055 7 infant 1.627273 0.0071750

6 0.120 8 infant 1.175000 0.0123025R

# abalone$Whole.weight.oz <- abalone$whole.weight*0.035

Plotting with Base R

Just like how there are multiple ways of wrangling data (base R functions vs Tidyverse functions), there are also multiple ways of generating plots. We will start with base R plots.

Before we get started, it is always good to take a peek at the data and remind ourselves of what we’re working with

R

head(abalone)

OUTPUT

Sex Length Diameter Height Whole.weight Shucked.weight Viscera.weight

1 M 0.455 0.365 0.095 0.5140 0.2245 0.1010

2 M 0.350 0.265 0.090 0.2255 0.0995 0.0485

3 F 0.530 0.420 0.135 0.6770 0.2565 0.1415

4 M 0.440 0.365 0.125 0.5160 0.2155 0.1140

5 I 0.330 0.255 0.080 0.2050 0.0895 0.0395

6 I 0.425 0.300 0.095 0.3515 0.1410 0.0775

Shell.weight Rings maturity Percent.weight

1 0.150 15 mature 1.496667

2 0.070 7 mature 1.421429

3 0.210 9 mature 1.221429

4 0.155 10 mature 1.390323

5 0.055 7 infant 1.627273

6 0.120 8 infant 1.175000Remember that the first column of abalone Sex was originally were character values but we wrangled this data into factors to recognize that there are relationships between observations with the same values (ie. all the abalone with a value “M” in the Sex column share the same biological Sex)

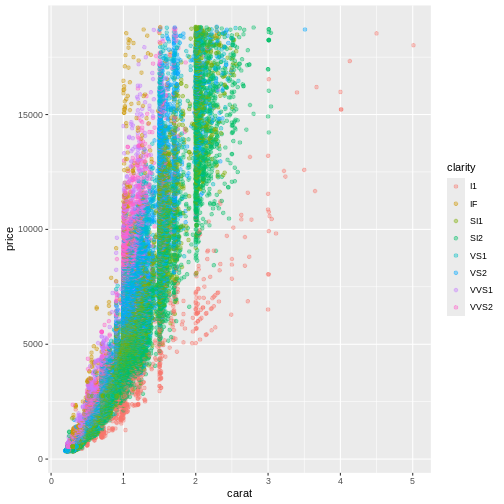

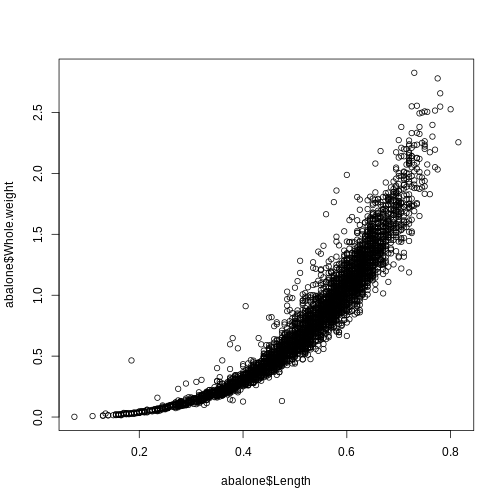

Base R plots are great for taking a quick peek at your data

R

plot(abalone$Length, abalone$Whole.weight)

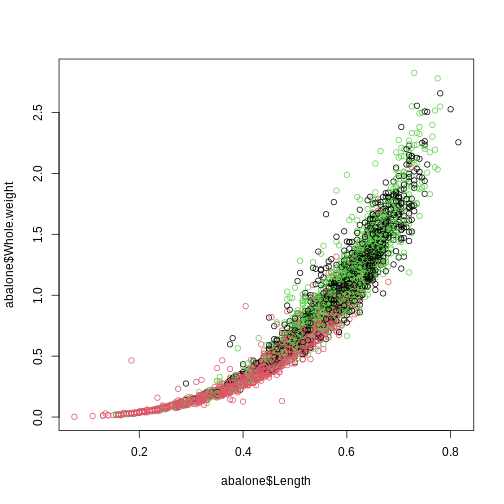

R

plot(abalone$Length, abalone$Whole.weight, col = abalone$Sex)

Note that you cannot color on a column of categorical data if it is not a factor because each entry is considered unique, there are no shared characteristics between the observations.

It can be confusing to figure out which color corresponds to which category in base R.

R

class(abalone$Sex)

OUTPUT

[1] "factor"R

levels(abalone$Sex)

OUTPUT

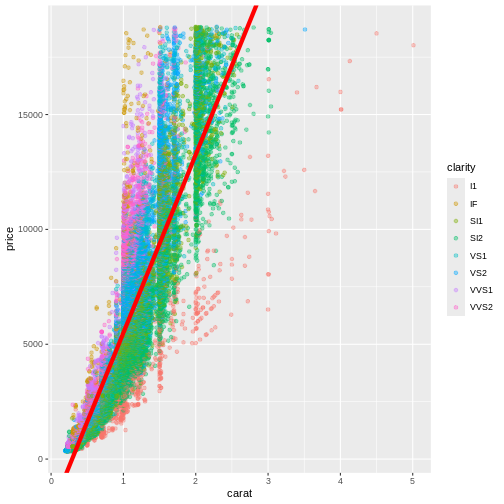

[1] "F" "I" "M"Let’s make a table to specify the color we want each level to be

R

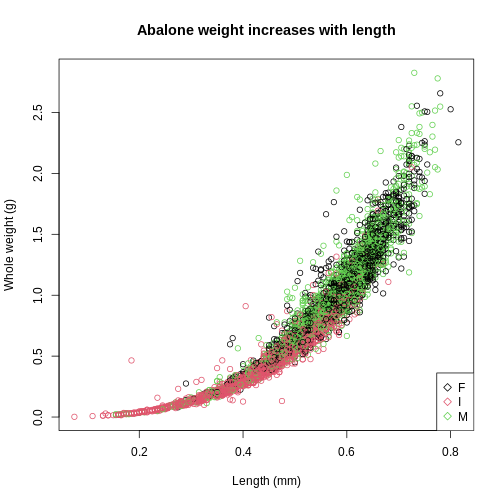

plot(abalone$Length, abalone$Whole.weight, col=abalone$Sex,

main = "Abalone weight increases with length",

xlab = "Length (mm)",

ylab = "Whole weight (g)")

legend(x="bottomright",

legend = levels(abalone$Sex),

col = 1:3,

pch = 5

)

Base R plots use layers so the base plot() must be

created first, before the legend() layer is added on

top.

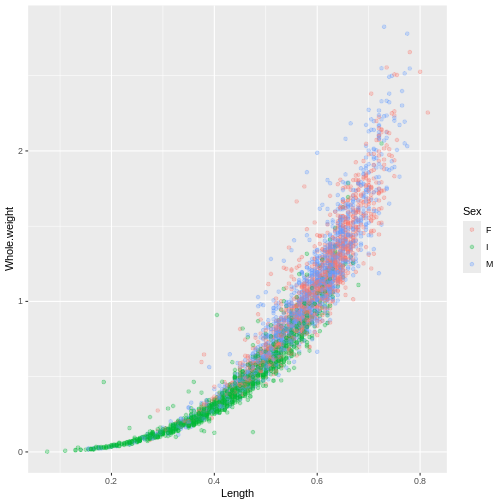

I stands for infant so it makes sense that they would be smaller in weight and length compared to the mature abalone.

Before we move on to the next type of plot, let’s customize it a bit more by cleaning up the axis

Scatterplot with ggplot

ggplot() was created to support customizable and

reproducible plots. The way that the ggplot() function

accepts the data is much different from the base R plot()

function.

The both columns of data must be in the same dataframe and specified

in the data parameter. Then, the x and y axis must be specified

using the aesthetic aes parameter. The base

ggplot() call only holds the data, the geometry or format

of the plot must be further specified by a separate call.

While commas , separate the parameters in a function,

plus signs + are used to specify different layers of the

plot.

This is the basic template for ggplots:

ggplot(data = , mapping = aes(

)) + ()

R

library(ggplot2)

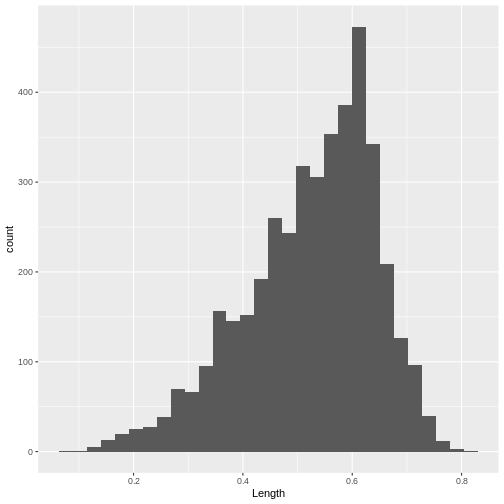

A single continuous variable can be displayed using a histogram.

R

ggplot(data = abalone, mapping = aes(x=Length)) +

geom_histogram()

OUTPUT

`stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

R

nrow(abalone)

OUTPUT

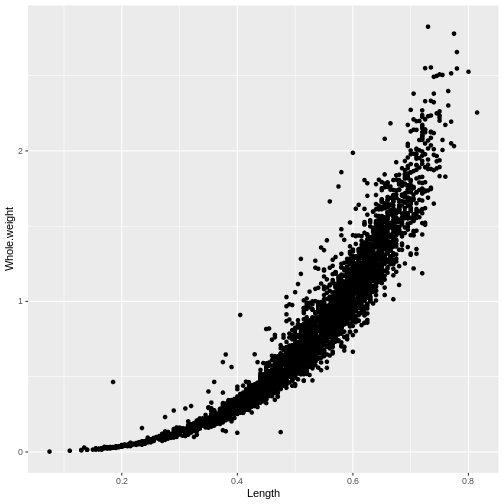

[1] 4177Two continuous variables can be contrasted using a point or scatter plot.

R

ggplot(abalone, aes(x = Length, y = Whole.weight)) +

geom_point()

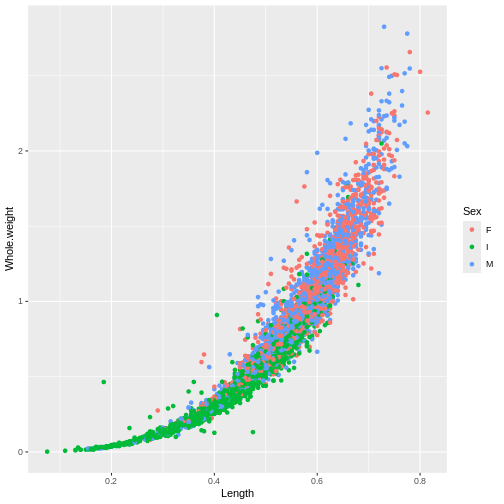

It is a lot simpler to add color to ggplots

R

ggplot(abalone, aes(x = Length, y = Whole.weight, col = Sex)) +

geom_point()

There’s a lot of dots that are piling up on top of each other so we

can change the alpha value to modify the transparency. Remember, you can

always look up more information about each function using the

? or looking online! No need to memorize everything!

R

ggplot(abalone, aes(x = Length, y = Whole.weight, col = Sex)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.3)

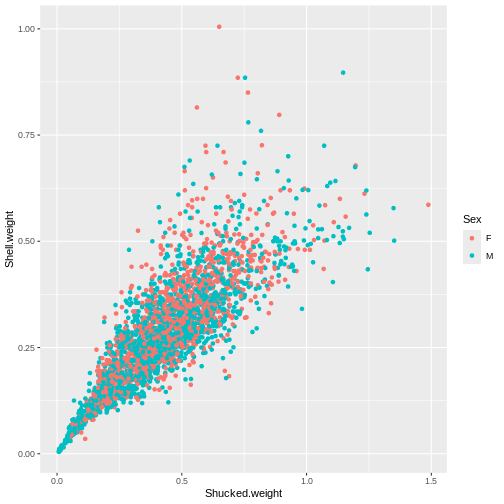

Exercise

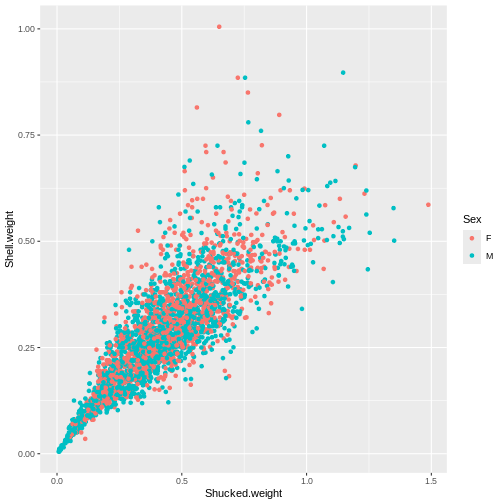

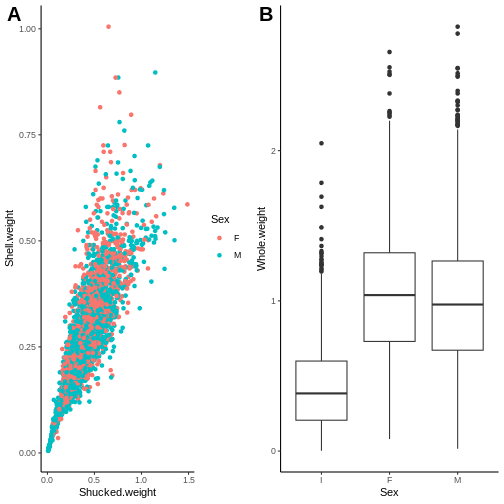

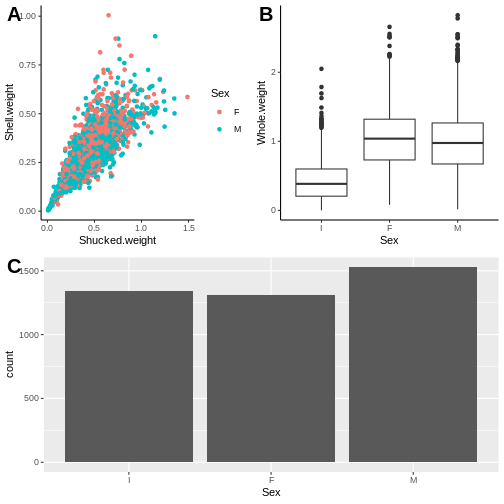

Create a plot to investigate the relationship between the shucked weight and the shell weight of ONLY adult abalone (exclude the infant abalones). Color the plot by Sex, do you notice any difference between the two?

R

abalone_MF <- abalone[abalone$Sex %in% c("M", "F"), ]

ggplot(abalone_MF, aes(x=Shucked.weight, y = Shell.weight, col = Sex)) +

geom_point()

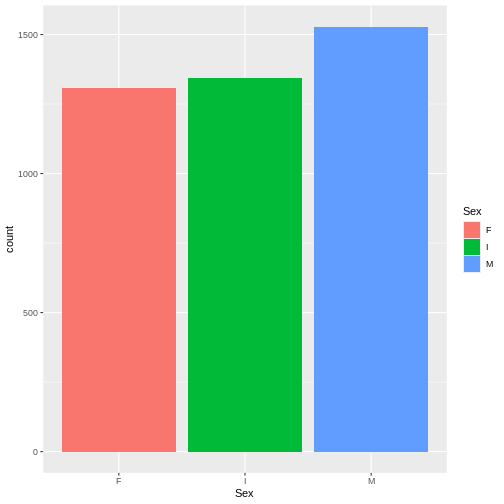

Let’s take a closer look at categorical data. One categorical data can be displayed with a bar plot. This is helpful when we are looking to see if we have equal representation in each of the sample groups.

R

ggplot(abalone, aes(x= Sex, fill = Sex)) +

geom_bar()

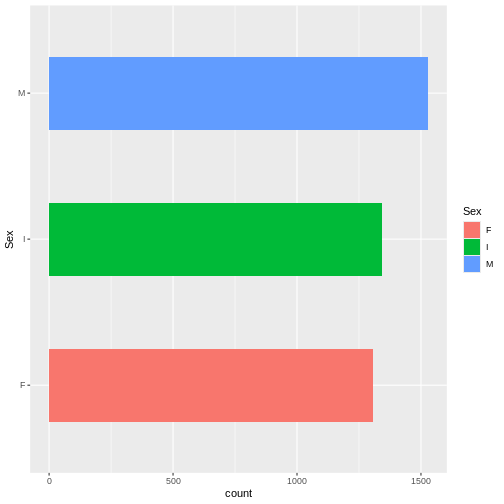

Bar plots can also be easily modified.

R

ggplot(abalone, aes(x= Sex, fill = Sex)) +

geom_bar(width = 0.5) +

coord_flip()

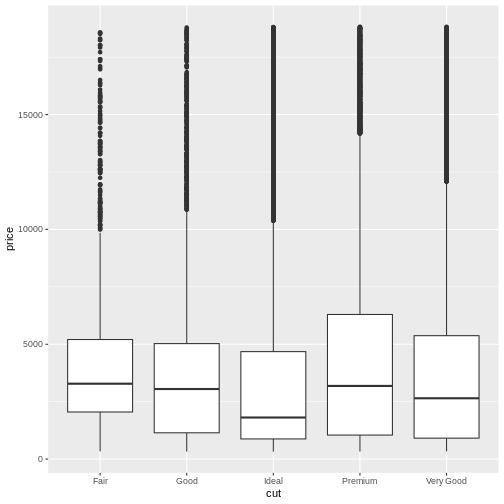

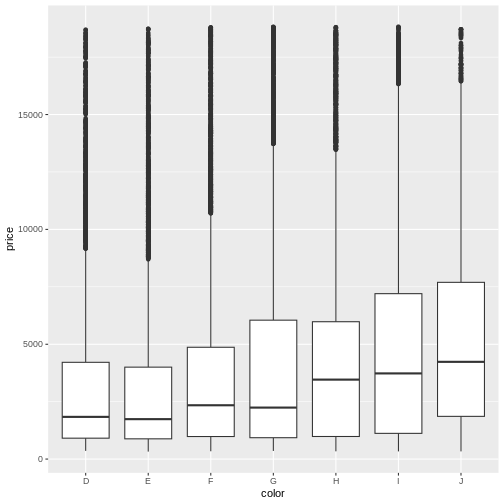

Lastly, boxplots are used to describe the relationship between a continuous and a categorical variable.

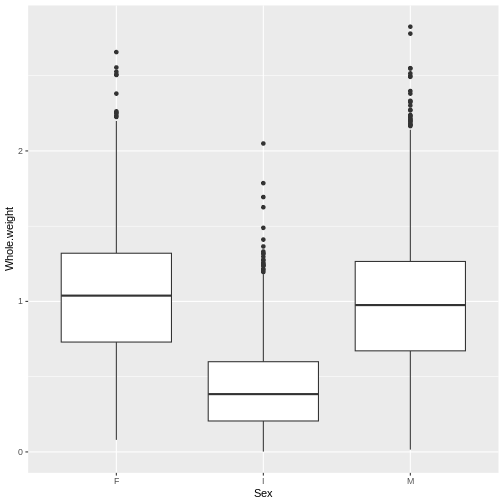

R

ggplot(abalone, aes(x = Sex, y = Whole.weight)) +

geom_boxplot()

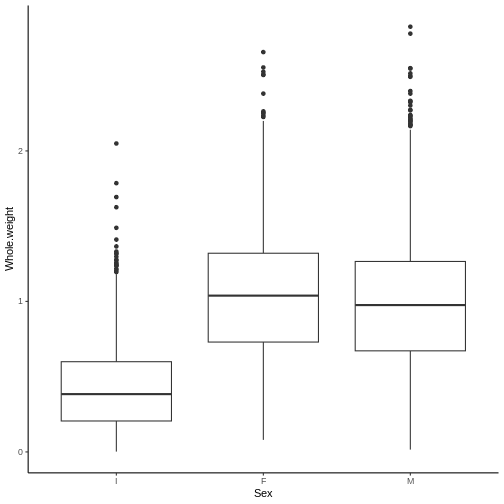

This more clearly shows that the weight distribution is comparable between the males and females. However, it would be clearer to have the F and M bars adjacent for comparison.

R

levels(abalone$Sex)

OUTPUT

[1] "F" "I" "M"R

abalone$Sex <- factor(abalone$Sex, levels = c("I", "F", "M"))

ggplot(abalone, aes(x = Sex, y = Whole.weight)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_classic()

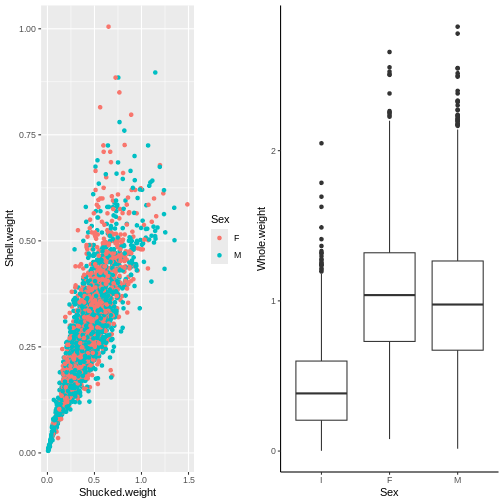

Multi-panel plots with ggplot

Plots can be saved as objects

R

p1 <- ggplot(abalone_MF, aes(x=Shucked.weight, y = Shell.weight, col = Sex)) +

geom_point()

p2 <- ggplot(abalone, aes(x = Sex, y = Whole.weight)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_classic()

p1

Rather than flipping between separating plots and stitching them

together afterwards in a photo editor, we can arrange them into a figure

panel all together in R

Rather than flipping between separating plots and stitching them

together afterwards in a photo editor, we can arrange them into a figure

panel all together in R

R

#install.packages("cowplot")

library(cowplot)

OUTPUT

Attaching package: 'cowplot'OUTPUT

The following object is masked from 'package:lubridate':

stampR

plot_grid(p1, p2)

Let’s clean this up a bit

Let’s clean this up a bit

R

top_row <- plot_grid(p1 + theme_classic(),

p2,

labels = c("A", "B"),

label_size = 20)

top_row

Adding a third plot to play around with the distribution between

panels

Adding a third plot to play around with the distribution between

panels

We want p1 to be larger by itself in the top row and then p2 and p3 split in the bottom row.

R

p3 <- ggplot(abalone, aes(Sex)) + geom_bar()

plot_grid(top_row, p3, ncol=1,

labels = c("", "C"),

label_size = 20)

Exporting plots

R

getwd()

OUTPUT

[1] "/home/runner/work/INR_2024_Recreate_Carpentries/INR_2024_Recreate_Carpentries/site/built"R

png(file = "INR_fig1.png", bg = "transparent")

top_row

dev.off()

OUTPUT

png

2 Day 1 Project

For this mini guided project, we will be working with a dataset quantifying water quality that is publicly available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/adityakadiwal/water-potability?resource=download

Here is some description of the data:

Access to safe drinking-water is essential to health, a basic human right and a component of effective policy for health protection. This is important as a health and development issue at a national, regional and local level. In some regions, it has been shown that investments in water supply and sanitation can yield a net economic benefit, since the reductions in adverse health effects and health care costs outweigh the costs of undertaking the interventions. Content

The water_potability.csv file contains water quality metrics for 3276 different water bodies. More information about each of the columns can be found in the link above

pH value Hardness Solids (Total dissolved solids - TDS) Chloramines Sulfate Conductivity Organic_carbon Trihalomethanes Turbidity Potability

Insert a code chunk underneath each step to carry out the instruction.

Read in the “water_potability.csv” data into an object called data Check the object you created by printing out the first 10 rows and applying the summary function.

Notice that the pH column contains a couple hundred NA values. NA are special values in R (like how “pi” is preset to a value of 3.14159…) to indicate that there is missing data, or it is not available. There are also some NAs in the Sulfate and Trihalomethanes columns.

Create new object called water_df that only contains complete observations.

Hint: take a look at the function called na.omit(). In

most cases, someone’s already done what you’ve wanted to do so there may

already be code or functions that you can adapt and use!

- The Potability column has two possible values: 1 means Potable and 0 means Not potable.

It is read in by default as a character vector. Convert this column to a factor.

- WHO has recommended maximum permissible limit of pH in drinking water from 6.5 to 8.5.

Create a new column within the water_df object called

ph_category in which:

- Observations with a pH less than 6.5 have a value of

acidicin theph_category - Observations with a pH betwee 6.5 - 8.5 have a value of

permissiblein theph_category - Observations with a pH greater than 8.5 have a value of

basicin theph_category

There are multiple ways to do this, give it a go! You can’t break the object - if you ever feel like you need a reset, you can always repeat step 1 to read in the object again.

Use table() or summary() to check the

values in the ph_category column

- Create a plot to double check if the annotations in the

ph_categorycolumn were applied correctly. Make sure to represent both thephandph_categorycolumns.

You’re welcome to use base R or ggplot functions. There are multiple ways of representing these two columns. ggplot is slightly preferred because of its increased customization so it’s good to get some practice with it!

- The levels of sulfates and water hardness cause by salts should be minimized in order to be safe for consumption.

Create a plot with the level of water hardness on the x axis and sulphate on the y axis colored by the Potability column.

Try applying the facet_grid() layer to the plot in order

to group the plots by a factor. Make sure to use the ~

before the column name!

(Note - the data is quite messy so don’t worry if the results do not separate as much as you would like - real data is messy!)

This is a lesson created via The Carpentries Workbench. It is written in Pandoc-flavored Markdown for static files and R Markdown for dynamic files that can render code into output. Please refer to the Introduction to The Carpentries Workbench for full documentation.

What you need to know is that there are three sections required for a valid Carpentries lesson template:

-

questionsare displayed at the beginning of the episode to prime the learner for the content. -

objectivesare the learning objectives for an episode displayed with the questions. -

keypointsare displayed at the end of the episode to reinforce the objectives.

Challenge 1: Can you do it?

What is the output of this command?

R

paste("This", "new", "lesson", "looks", "good")

OUTPUT

[1] "This new lesson looks good"Challenge 2: how do you nest solutions within challenge blocks?

You can add a line with at least three colons and a

solution tag.

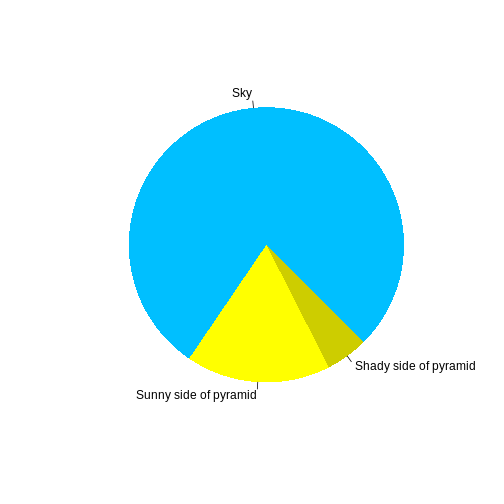

Figures

You can also include figures generated from R Markdown:

R

pie(

c(Sky = 78, "Sunny side of pyramid" = 17, "Shady side of pyramid" = 5),

init.angle = 315,

col = c("deepskyblue", "yellow", "yellow3"),

border = FALSE

)

Or you can use standard markdown for static figures with the following syntax:

{alt='alt text for accessibility purposes'}

Callout

Callout sections can highlight information.

They are sometimes used to emphasise particularly important points but are also used in some lessons to present “asides”: content that is not central to the narrative of the lesson, e.g. by providing the answer to a commonly-asked question.

Math

One of our episodes contains \(\LaTeX\) equations when describing how to create dynamic reports with {}, so we now use mathjax to describe this:

$\alpha = \dfrac{1}{(1 - \beta)^2}$ becomes: \(\alpha = \dfrac{1}{(1 - \beta)^2}\)

Cool, right?

Key Points

This comes from the file you are summarizing from, this is in the day-1.Rmd file

Run

sandpaper::check_lesson()to identify any issues with your lessonRun

sandpaper::build_lesson()to preview your lesson locally

Content from Day 2

Last updated on 2025-01-07 | Edit this page

Lecture Files

Below is the rendered and completed version of Day 2’s R Markdown file. Begin with the empty version here. You will also need to download the following datasets:

All Introduction to R (2024) course materials are available here.

Day 1 Project

For this mini guided project, we will be working with a dataset quantifying water quality that is publicly available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/adityakadiwal/water-potability?resource=download

Here is some description of the data:

Access to safe drinking-water is essential to health, a basic human right and a component of effective policy for health protection. This is important as a health and development issue at a national, regional and local level. In some regions, it has been shown that investments in water supply and sanitation can yield a net economic benefit, since the reductions in adverse health effects and health care costs outweigh the costs of undertaking the interventions. Content

The water_potability.csv file contains water quality metrics for 3276 different water bodies. More information about each of the columns can be found in the link above

pH value Hardness Solids (Total dissolved solids - TDS) Chloramines Sulfate Conductivity Organic_carbon Trihalomethanes Turbidity Potability

Insert a code chunk underneath each step to carry out the instruction.

- Read in the “water_potability.csv” data into an object called data Check the object you created by printing out the first 10 rows and applying the summary function.

R

data <- read.csv("data/water_potability.csv")

head(data, n=10)

OUTPUT

ph Hardness Solids Chloramines Sulfate Conductivity Organic_carbon

1 NA 204.8905 20791.32 7.300212 368.5164 564.3087 10.379783

2 3.716080 129.4229 18630.06 6.635246 NA 592.8854 15.180013

3 8.099124 224.2363 19909.54 9.275884 NA 418.6062 16.868637

4 8.316766 214.3734 22018.42 8.059332 356.8861 363.2665 18.436524

5 9.092223 181.1015 17978.99 6.546600 310.1357 398.4108 11.558279

6 5.584087 188.3133 28748.69 7.544869 326.6784 280.4679 8.399735

7 10.223862 248.0717 28749.72 7.513408 393.6634 283.6516 13.789695

8 8.635849 203.3615 13672.09 4.563009 303.3098 474.6076 12.363817

9 NA 118.9886 14285.58 7.804174 268.6469 389.3756 12.706049

10 11.180284 227.2315 25484.51 9.077200 404.0416 563.8855 17.927806

Trihalomethanes Turbidity Potability

1 86.99097 2.963135 0

2 56.32908 4.500656 0

3 66.42009 3.055934 0

4 100.34167 4.628771 0

5 31.99799 4.075075 0

6 54.91786 2.559708 0

7 84.60356 2.672989 0

8 62.79831 4.401425 0

9 53.92885 3.595017 0

10 71.97660 4.370562 0R

data[1:10, ]

OUTPUT

ph Hardness Solids Chloramines Sulfate Conductivity Organic_carbon

1 NA 204.8905 20791.32 7.300212 368.5164 564.3087 10.379783

2 3.716080 129.4229 18630.06 6.635246 NA 592.8854 15.180013

3 8.099124 224.2363 19909.54 9.275884 NA 418.6062 16.868637

4 8.316766 214.3734 22018.42 8.059332 356.8861 363.2665 18.436524

5 9.092223 181.1015 17978.99 6.546600 310.1357 398.4108 11.558279

6 5.584087 188.3133 28748.69 7.544869 326.6784 280.4679 8.399735

7 10.223862 248.0717 28749.72 7.513408 393.6634 283.6516 13.789695

8 8.635849 203.3615 13672.09 4.563009 303.3098 474.6076 12.363817

9 NA 118.9886 14285.58 7.804174 268.6469 389.3756 12.706049

10 11.180284 227.2315 25484.51 9.077200 404.0416 563.8855 17.927806

Trihalomethanes Turbidity Potability

1 86.99097 2.963135 0

2 56.32908 4.500656 0

3 66.42009 3.055934 0

4 100.34167 4.628771 0

5 31.99799 4.075075 0

6 54.91786 2.559708 0

7 84.60356 2.672989 0

8 62.79831 4.401425 0

9 53.92885 3.595017 0

10 71.97660 4.370562 0- Notice that the pH column contains a couple hundred NA values. NA are special values in R (like how “pi” is preset to a value of 3.14159…) to indicate that there is missing data, or it is not available. There are also some NAs in the Sulfate and Trihalomethanes columns.

Create new object called water_df that only contains complete observations.

Hint: take a look at the function called na.omit(). In

most cases, someone’s already done what you’ve wanted to do so there may

already be code or functions that you can adapt and use!

R

water_df <- na.omit(data)

summary(data)

OUTPUT

ph Hardness Solids Chloramines

Min. : 0.000 Min. : 47.43 Min. : 320.9 Min. : 0.352

1st Qu.: 6.093 1st Qu.:176.85 1st Qu.:15666.7 1st Qu.: 6.127

Median : 7.037 Median :196.97 Median :20927.8 Median : 7.130

Mean : 7.081 Mean :196.37 Mean :22014.1 Mean : 7.122

3rd Qu.: 8.062 3rd Qu.:216.67 3rd Qu.:27332.8 3rd Qu.: 8.115

Max. :14.000 Max. :323.12 Max. :61227.2 Max. :13.127

NA's :491

Sulfate Conductivity Organic_carbon Trihalomethanes

Min. :129.0 Min. :181.5 Min. : 2.20 Min. : 0.738

1st Qu.:307.7 1st Qu.:365.7 1st Qu.:12.07 1st Qu.: 55.845

Median :333.1 Median :421.9 Median :14.22 Median : 66.622

Mean :333.8 Mean :426.2 Mean :14.28 Mean : 66.396

3rd Qu.:360.0 3rd Qu.:481.8 3rd Qu.:16.56 3rd Qu.: 77.337

Max. :481.0 Max. :753.3 Max. :28.30 Max. :124.000

NA's :781 NA's :162

Turbidity Potability

Min. :1.450 Min. :0.0000

1st Qu.:3.440 1st Qu.:0.0000

Median :3.955 Median :0.0000

Mean :3.967 Mean :0.3901

3rd Qu.:4.500 3rd Qu.:1.0000

Max. :6.739 Max. :1.0000

R

summary(water_df)

OUTPUT

ph Hardness Solids Chloramines

Min. : 0.2275 Min. : 73.49 Min. : 320.9 Min. : 1.391

1st Qu.: 6.0897 1st Qu.:176.74 1st Qu.:15615.7 1st Qu.: 6.139

Median : 7.0273 Median :197.19 Median :20933.5 Median : 7.144

Mean : 7.0860 Mean :195.97 Mean :21917.4 Mean : 7.134

3rd Qu.: 8.0530 3rd Qu.:216.44 3rd Qu.:27182.6 3rd Qu.: 8.110

Max. :14.0000 Max. :317.34 Max. :56488.7 Max. :13.127

Sulfate Conductivity Organic_carbon Trihalomethanes

Min. :129.0 Min. :201.6 Min. : 2.20 Min. : 8.577

1st Qu.:307.6 1st Qu.:366.7 1st Qu.:12.12 1st Qu.: 55.953

Median :332.2 Median :423.5 Median :14.32 Median : 66.542

Mean :333.2 Mean :426.5 Mean :14.36 Mean : 66.401

3rd Qu.:359.3 3rd Qu.:482.4 3rd Qu.:16.68 3rd Qu.: 77.292

Max. :481.0 Max. :753.3 Max. :27.01 Max. :124.000

Turbidity Potability

Min. :1.450 Min. :0.0000

1st Qu.:3.443 1st Qu.:0.0000

Median :3.968 Median :0.0000

Mean :3.970 Mean :0.4033

3rd Qu.:4.514 3rd Qu.:1.0000

Max. :6.495 Max. :1.0000 R

dim(data)

OUTPUT

[1] 3276 10R

dim(water_df)

OUTPUT

[1] 2011 10- The Potability column has two possible values: 1 means Potable and 0 means Not potable.

It is read in by default as a character vector. Convert this column to a factor.

R

water_df$Potability <- as.factor(water_df$Potability)

head(water_df)

OUTPUT

ph Hardness Solids Chloramines Sulfate Conductivity Organic_carbon

4 8.316766 214.3734 22018.42 8.059332 356.8861 363.2665 18.436524

5 9.092223 181.1015 17978.99 6.546600 310.1357 398.4108 11.558279

6 5.584087 188.3133 28748.69 7.544869 326.6784 280.4679 8.399735

7 10.223862 248.0717 28749.72 7.513408 393.6634 283.6516 13.789695

8 8.635849 203.3615 13672.09 4.563009 303.3098 474.6076 12.363817

10 11.180284 227.2315 25484.51 9.077200 404.0416 563.8855 17.927806

Trihalomethanes Turbidity Potability

4 100.34167 4.628771 0

5 31.99799 4.075075 0

6 54.91786 2.559708 0

7 84.60356 2.672989 0

8 62.79831 4.401425 0

10 71.97660 4.370562 0R

table(water_df$Potability)

OUTPUT

0 1

1200 811 - WHO has recommended maximum permissible limit of pH in drinking water from 6.5 to 8.5.

Create a new column within the water_df object called

ph_category in which:

- Observations with a pH less than 6.5 have a value of

acidicin theph_category - Observations with a pH betwee 6.5 - 8.5 have a value of

permissiblein theph_category - Observations with a pH greater than 8.5 have a value of

basicin theph_category

There are multiple ways to do this, give it a go! You can’t break the object - if you ever feel like you need a reset, you can always repeat step 1 to read in the object again.

Use table() or summary() to check the

values in the ph_category column

R

water_df$ph_category <- "permissible"

water_df$ph_category[water_df$ph < 6.5] <- "acidic"

water_df$ph_category[water_df$ph > 8.5] <- "basic"

table(water_df$ph_category)

OUTPUT

acidic basic permissible

692 358 961 R

nrow(water_df[water_df$ph <6.5, ])

OUTPUT

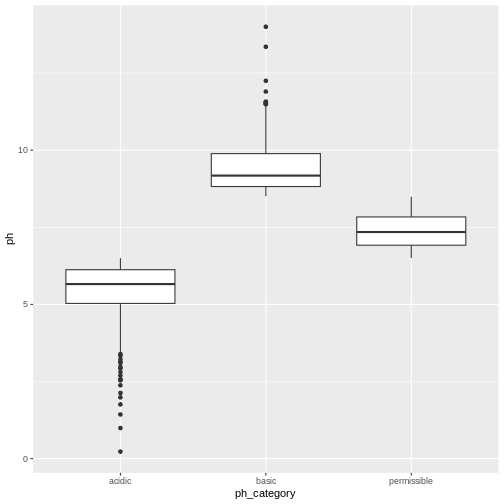

[1] 692- Create a plot to double check if the annotations in the

ph_categorycolumn were applied correctly. Make sure to represent both thephandph_categorycolumns.

You’re welcome to use base R or ggplot functions. There are multiple ways of representing these two columns. ggplot is slightly preferred because of its increased customization so it’s good to get some practice with it!

R

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(water_df, aes(x=ph_category, y=ph)) +

geom_boxplot()

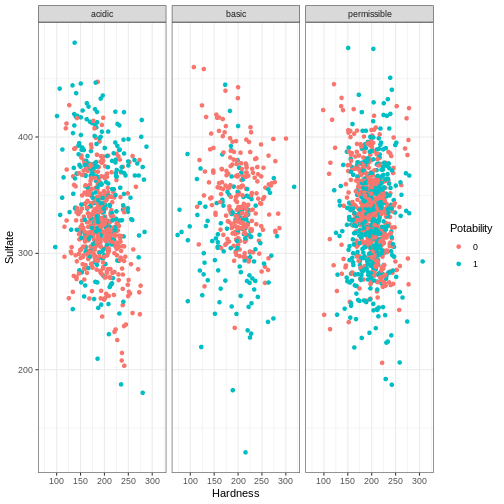

- The levels of sulfates and water hardness cause by salts should be minimized in order to be safe for consumption.

Create a plot with the level of water hardness on the x axis and sulphate on the y axis colored by the Potability column.

Try applying the facet_grid() layer to the plot in order

to group the plots by a factor. Make sure to use the ~

before the column name!

(Note - the data is quite messy so don’t worry if the results do not separate as much as you would like - real data is messy!)

R

ggplot(water_df, aes(x = Hardness, y = Sulfate, col = Potability)) +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(~ph_category) + theme_bw()

Review with Datasaurus Dozen

The Datasaurus Dozen dataset is a handful of data points that

complement the dplyr package. Aside from functions,

packages can also import objects.

R

#install.packages("datasauRus")

library(datasauRus)

library(tidyverse)

OUTPUT

── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ tibble 3.2.1

✔ purrr 1.0.2 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorsR

summary(datasaurus_dozen)

OUTPUT

dataset x y

Length:1846 Min. :15.56 Min. : 0.01512

Class :character 1st Qu.:41.07 1st Qu.:22.56107

Mode :character Median :52.59 Median :47.59445

Mean :54.27 Mean :47.83510

3rd Qu.:67.28 3rd Qu.:71.81078

Max. :98.29 Max. :99.69468 R

datasaurus_dozen$dataset <- as.factor(datasaurus_dozen$dataset)

tail(datasaurus_dozen)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 6 × 3

dataset x y

<fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 wide_lines 34.7 19.6

2 wide_lines 33.7 26.1

3 wide_lines 75.6 37.1

4 wide_lines 40.6 89.1

5 wide_lines 39.1 96.5

6 wide_lines 34.6 89.6R

table(datasaurus_dozen$dataset)

OUTPUT

away bullseye circle dino dots h_lines high_lines

142 142 142 142 142 142 142

slant_down slant_up star v_lines wide_lines x_shape

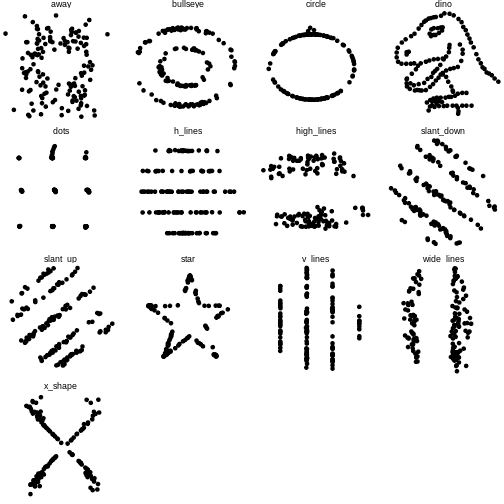

142 142 142 142 142 142 There are 13 different datasets in this one object. We will use tidyverse functions to take an overview look at the object, grouped by the datasets.

R

datasaurus_dozen %>%

group_by(dataset) %>%

summarize(mean_x = mean(x),

mean_y = mean(y),

std_dev_x = sd(x),

std_dev_y = sd(y))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 13 × 5

dataset mean_x mean_y std_dev_x std_dev_y

<fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 away 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

2 bullseye 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

3 circle 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

4 dino 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

5 dots 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

6 h_lines 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

7 high_lines 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

8 slant_down 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

9 slant_up 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

10 star 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

11 v_lines 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

12 wide_lines 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9

13 x_shape 54.3 47.8 16.8 26.9All of the datasets have roughly the same mean and standard deviation along both the x and y axis.

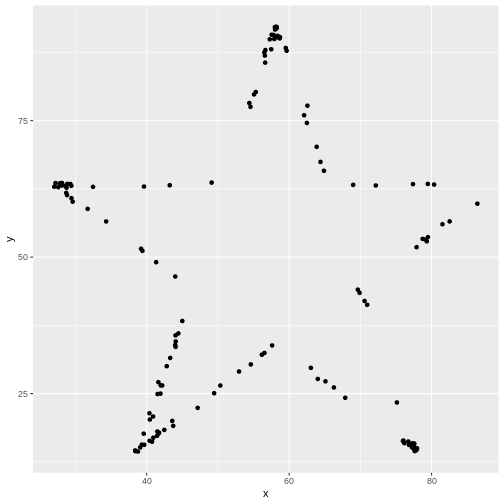

Let’s take a look the data graphically. We will use

filter to extract the rows belonging to one dataset and

then pipe that directly into a ggplot. Both dplyr and ggplot are

developed within “the Tidyverse” and can use pipes, but you may not be

able to pipe in base R functions or functions from different

packages.

R

datasaurus_dozen %>%

filter(dataset == "star") %>%

ggplot(aes(x=x, y=y)) + # PLUS SIGN, NOT PIPE FOR THIS ONE

geom_point()

Tidyverse’s data wranging packages use the pipe %>%

to move the previous output to the next line, where as ggplot uses the

plus sign +

Try editing the code above to display different datasets. Notice how different groups of data points can all give similar statistical summaries - so it’s always a good choice to visualize your data rather than relying on just numbers.

If we wanted to take a look at all of the datasets at once, we can

also use the facet_wrap() function.

R

datasaurus_dozen %>%

#filter(dataset == "star") %>% REMOVE THIS ROW

ggplot(aes(x=x, y=y)) +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(~dataset)+ theme_void() # ADD THIS LINE

R

head(datasaurus_dozen)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 6 × 3

dataset x y

<fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 dino 55.4 97.2

2 dino 51.5 96.0

3 dino 46.2 94.5

4 dino 42.8 91.4

5 dino 40.8 88.3

6 dino 38.7 84.9Genearlizable code

A major strength of programming is the ability to automate repetitive tasks. As a general rule of thumb, if you need to do a task more than three times (ex. analyzing multiple PCR plates or integrating clinical data from multiple days), it is worth it to invest time to write generalizable code or a custom function.

Now that we’re getting comfortable writing code, we will spend some time revisiting code that we wrote to make them generalizable and even better! Generalizable means that the code is flexible and can be applied to multiple similar objects. For example, if we’re running a clinical study and we have patient demographic data from multiple sites, we want to check that the mean patient demographic is comparable between sites by creating similar plots of each hospital site to compare. If we write code for one location and then copy and paste it into another code chunk to apply to the next location, the code may require some modification before it works.

Generalizable code begins at data collection. Depending on your workflow, you may or may not be able to influence this stage of the analysis. If possible, it is best practice to keep the column names and entries for categorical variables consistent. For example, when recording the age of patients, “6”, “6”, “six”, and “Six” are all considered different levels of the factor so you will need to either make sure data collection is consistent or check and correct these inconsistencies in your code. Get into a habit of checking your work. Whether it is code you’ve written yourself, code you you’ve been sent by a collaborator, or published data from a biobank - never assume the data is as you predicted.

Generalizable plots

Remember when we edited our code to test out multiple datasets in the datasaurus dozen object? Perhaps you copy and pasted the code several time and changed the column name? This is not optimal because if you need to change the code in one instance (for example changing the x-axis label), you’ll need to revisit ever instance that you copy and pasted to code to. This approach leads you vulnerable to errors when copy and pasting.

One way to make your code robust is to bring all the factors that need editing to the start of the data. This may seem cumbersome for such a simple example where we are only changing the dataset name, but we’ll return to this concept later with more complicated examples.

Let’s grab the code we used to make one plot earlier and modify it to be more generalizable

R

levels(datasaurus_dozen$dataset)

OUTPUT

[1] "away" "bullseye" "circle" "dino" "dots"

[6] "h_lines" "high_lines" "slant_down" "slant_up" "star"

[11] "v_lines" "wide_lines" "x_shape" R

dataset_name <- "dino" # ADD THIS LINE

datasaurus_dozen %>%

filter(dataset == dataset_name) %>% # Remove comment # CHANGE VARIABLE NAME

ggplot(aes(x=x, y=y)) +

geom_point() # REMOVE THE + at the end of the line

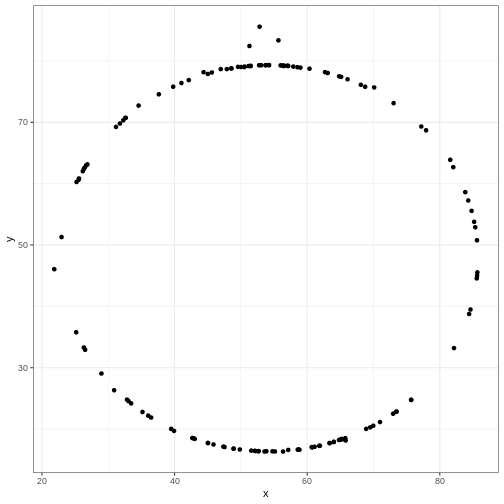

Once we have converted our code to a generalized format, we can convert it into a more versatile custom function!

Curly brackets are used for inputting multiple lines of code. It is generally attached to the function that proceeds it.

R

# dataset_name <- "dino" # ADD THIS LINE

dino_plot <- function(data_name) {

datasaurus_dozen %>%

filter(dataset == data_name) %>% # CHANGE ARGUMENT NAME

ggplot(aes(x=x, y=y)) +

geom_point() +

theme_bw()

}

dino_plot("dino")

R

dino_plot("circle")

Exercise

We’ve now encountered round brackets (), square brackets

[], and curly brackets{} - each have their own

distinct functions! Take a few moments to chat with your neighbors and

outline cases in which we’ve used each bracket and what is their role in

R syntax.

round brackets () come after a function, function will apply to whatever is in the brackets functionName(what is being acted on)

square brackets [] Indexing, locations object[position] dataframe[rows, cols]

curly brackets {} Used in function, indicate multiple lines of related code Rmd – indicates language in code chunk

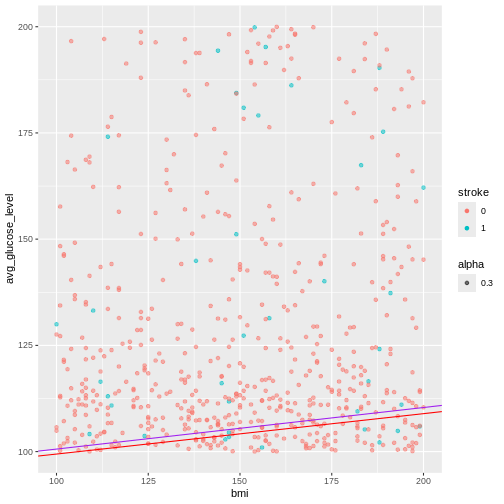

Dataset - Heart Stroke Preduction

The dataset we will be working with for today’s workshop contains clinical data collected with the aim of predicting whether a patient is likely to suffer a stroke.

The dataset can be found: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/fedesoriano/stroke-prediction-dataset

Here is some more information about the columns in this dataset:

- id: unique identifier

- gender: “Male”, “Female” or “Other”

- age: age of the patient

- hypertension: 0 if the patient doesn’t have hypertension, 1 if the patient has hypertension

- heart_disease: 0 if the patient doesn’t have any heart diseases, 1 if the patient has a heart disease

- ever_married: “No” or “Yes”

- work_type: “children”, “Govt_jov”, “Never_worked”, “Private” or “Self-employed”

- Residence_type: “Rural” or “Urban”

- avg_glucose_level: average glucose level in blood

- bmi: body mass index

- smoking_status: “formerly smoked”, “never smoked”, “smokes” or “Unknown”*

- stroke: 1 if the patient had a stroke or 0 if not *Note: “Unknown” in smoking_status means that the information is unavailable for this patient

Let’s get started!

Exercise

Reading in the dataset can be an intimidating step when you’re just

starting out with programming. Since this is a csv file, we can use the

appropriately named read.csv() function. In cases when you

have other file types such as .txt or .tab files that are tab

deliminated, there is also a read.table() function that is

more universal (but requires more parameters to let R know how your data

is stored).

Read in the healthcare-dataset-stroke-data.csv into an

object called heart. Check your object using head and/or

summary functions. Toggle a parameter called

stringsAsFactors to TRUE in order to

automatically import character values as factors rather than

characters

Hint: make sure the dataset is in the same directory or folder as this .Rmd file for ease of import

R

heart <- read.csv("data/healthcare-dataset-stroke-data.csv", stringsAsFactors=TRUE)

head(heart)

OUTPUT

id gender age hypertension heart_disease ever_married work_type

1 9046 Male 67 0 1 Yes Private

2 51676 Female 61 0 0 Yes Self-employed

3 31112 Male 80 0 1 Yes Private

4 60182 Female 49 0 0 Yes Private

5 1665 Female 79 1 0 Yes Self-employed

6 56669 Male 81 0 0 Yes Private

Residence_type avg_glucose_level bmi smoking_status stroke

1 Urban 228.69 36.6 formerly smoked 1

2 Rural 202.21 N/A never smoked 1

3 Rural 105.92 32.5 never smoked 1

4 Urban 171.23 34.4 smokes 1

5 Rural 174.12 24 never smoked 1

6 Urban 186.21 29 formerly smoked 1R

str(heart)

OUTPUT

'data.frame': 5110 obs. of 12 variables:

$ id : int 9046 51676 31112 60182 1665 56669 53882 10434 27419 60491 ...

$ gender : Factor w/ 6 levels "female","Female",..: 4 2 4 2 2 4 4 2 2 2 ...

$ age : num 67 61 80 49 79 81 74 69 59 78 ...

$ hypertension : Factor w/ 4 levels "0","1","10","10+D4972": 1 1 1 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 ...

$ heart_disease : int 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 ...

$ ever_married : Factor w/ 2 levels "No","Yes": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 ...

$ work_type : Factor w/ 8 levels "children","Govt_job",..: 5 7 5 5 7 5 5 5 5 5 ...

$ Residence_type : Factor w/ 2 levels "Rural","Urban": 2 1 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 ...

$ avg_glucose_level: num 229 202 106 171 174 ...

$ bmi : Factor w/ 419 levels "10.3","11.3",..: 240 419 199 218 114 164 148 102 419 116 ...

$ smoking_status : Factor w/ 4 levels "formerly smoked",..: 1 2 2 3 2 1 2 2 4 4 ...

$ stroke : int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...R

# Hypertension has values that are typos, need to be removed

table(heart$hypertension)

OUTPUT

0 1 10 10+D4972

4612 493 4 1 R

# Stroke and heart.disease need to be categorical

summary(heart$stroke)

OUTPUT

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.04873 0.00000 1.00000 R

# Gender has some variability

table(heart$gender)

OUTPUT

female Female male Male meal Other

7 2987 6 2108 1 1 R

# Abnormal BMI value AND convert from factor to numeric

summary(heart$bmi)

OUTPUT

N/A 28.7 28.4 26.1 26.7 27.6 27.7 23.4 27.3 27

201 41 38 37 37 37 37 36 36 35

25.1 26.4 26.9 25.5 23.5 24.8 28.9 22.2 26.5 28.3

34 34 34 33 31 31 31 30 30 30

29.4 30.3 31.4 24.2 26.6 27.5 28.1 29.1 24 24.1

30 30 30 29 29 29 29 29 28 28

25.3 27.1 27.9 28 32.3 21.5 23 24.9 25 26.2

28 28 28 28 28 27 27 27 27 27

28.5 28.6 29.7 30 30.9 31.5 24.3 24.5 25.4 28.8

27 27 27 27 27 27 26 26 26 26

29 29.2 29.5 29.6 29.9 30.1 31.1 20.1 22.7 22.8

26 26 26 26 26 26 26 25 25 25

26 28.2 32.8 33.1 23.6 23.9 25.8 25.9 27.2 30.5

25 25 25 25 24 24 24 24 24 24

31.8 32.1 35.8 20.4 24.4 26.3 27.8 29.8 30.7 33.5

24 24 24 23 23 23 23 23 23 23

21.4 22.1 22.4 23.8 24.6 24.7 27.4 29.3 31 31.9

22 22 22 22 22 22 22 22 22 22

19.5 21.3 23.1 25.6 26.8 30.8 31.3 31.6 32 (Other)

21 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 2282 R

# Age, very low value of 0.08

str(heart)

OUTPUT

'data.frame': 5110 obs. of 12 variables:

$ id : int 9046 51676 31112 60182 1665 56669 53882 10434 27419 60491 ...

$ gender : Factor w/ 6 levels "female","Female",..: 4 2 4 2 2 4 4 2 2 2 ...

$ age : num 67 61 80 49 79 81 74 69 59 78 ...

$ hypertension : Factor w/ 4 levels "0","1","10","10+D4972": 1 1 1 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 ...

$ heart_disease : int 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 ...

$ ever_married : Factor w/ 2 levels "No","Yes": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 ...

$ work_type : Factor w/ 8 levels "children","Govt_job",..: 5 7 5 5 7 5 5 5 5 5 ...

$ Residence_type : Factor w/ 2 levels "Rural","Urban": 2 1 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 ...

$ avg_glucose_level: num 229 202 106 171 174 ...

$ bmi : Factor w/ 419 levels "10.3","11.3",..: 240 419 199 218 114 164 148 102 419 116 ...

$ smoking_status : Factor w/ 4 levels "formerly smoked",..: 1 2 2 3 2 1 2 2 4 4 ...

$ stroke : int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...Before we dive into this dataset, we get a very limited indication

that the object is read in correctly by checking the Environment panel -

you’ll notice the new heart appears under Data and it lets

us know that there are 5110 observations (number of patients) and 12

variables (number of clinical features with entries). You can also

double click the name of the object here to open up a view of the whole

dataset - caution that this can cause your machine to stall if the

dataset is exceptionally large and/or your machine is running on minimal

memory.

Exercise

Explore the dataset! Take a look at the columns and identify some potential issues with this dataset that either warrant further investigation or correction.

There is no universally right or wrong way to do this. Perhaps the only truly incorrect way of doing this is going through the dataset which is thousands of observations line by line.

Factors

The stringsAsFactors parameter takes care of the

character values but we still have some integer values that should be

interpreted as factors.

When deciding on whether a number is a factor or should be kept

numeric, consider if decimals/numbers-in-between make sense. The first

two entries for avg_glucose_level are 229 and 202 - a

glucose level in between would be reasonable. In contrast, the first to

entries for heart_disease are 1 and 0 - as these are coding

for having or not having the disorder, an entry of 1.2 does not make

sense.

Recall from the introduction to the dataset from above: 4) hypertension: 0 if the patient doesn’t have hypertension, 1 if the patient has hypertension 5) heart_disease: 0 if the patient doesn’t have any heart diseases, 1 if the patient has a heart disease 12) stroke: 1 if the patient had a stroke or 0 if not

R

heart$hypertension <- as.factor(heart$hypertension)

heart$heart_disease <- as.factor(heart$heart_disease)

heart$stroke <- as.factor(heart$stroke)

summary(heart)

OUTPUT

id gender age hypertension heart_disease

Min. : 67 female: 7 Min. : 0.08 0 :4612 0:4834

1st Qu.:17741 Female:2987 1st Qu.:25.00 1 : 493 1: 276

Median :36932 male : 6 Median :45.00 10 : 4

Mean :36518 Male :2108 Mean :43.23 10+D4972: 1

3rd Qu.:54682 meal : 1 3rd Qu.:61.00

Max. :72940 Other : 1 Max. :82.00

ever_married work_type Residence_type avg_glucose_level

No :1757 Private :2921 Rural:2514 Min. : 55.12

Yes:3353 Self-employed: 818 Urban:2596 1st Qu.: 77.25

children : 687 Median : 91.89

Govt_job : 656 Mean :106.15

Never_worked : 22 3rd Qu.:114.09

Private : 4 Max. :271.74

(Other) : 2

bmi smoking_status stroke

N/A : 201 formerly smoked: 885 0:4861

28.7 : 41 never smoked :1892 1: 249

28.4 : 38 smokes : 789

26.1 : 37 Unknown :1544

26.7 : 37

27.6 : 37

(Other):4719 Incomplete data

Firstly, we have to make a decision on how to handle missing values. We can either accept that some of the columns are incomplete or eliminate rows that do not have full data. Let’s evaluate which columns this affects

If you ever encounter missing data when you are entering data, use

NA.

R

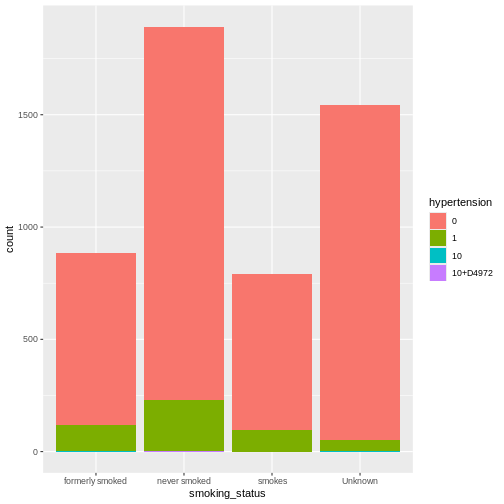

ggplot(heart, aes(x = smoking_status, fill = hypertension)) +

geom_bar()

R

prop.table(table(heart$smoking_status, heart$hypertension))

OUTPUT

0 1 10 10+D4972

formerly smoked 0.1497064579 0.0232876712 0.0001956947 0.0000000000

never smoked 0.3248532290 0.0448140900 0.0003913894 0.0001956947

smokes 0.1360078278 0.0183953033 0.0000000000 0.0000000000

Unknown 0.2919765166 0.0099804305 0.0001956947 0.0000000000Let’s use tidyverse to remove the rows in the

smoking_status column with a value of

Unknown.

R

dim(heart) # original 5110 rows

OUTPUT

[1] 5110 12R

table(heart$smoking_status) #1544 unknowns

OUTPUT

formerly smoked never smoked smokes Unknown

885 1892 789 1544 R

dim(filter(heart, !(smoking_status == "Unknown")))

OUTPUT

[1] 3566 12R

heart <- filter(heart, !(smoking_status == "Unknown"))

summary(heart$smoking_status)

OUTPUT

formerly smoked never smoked smokes Unknown

885 1892 789 0 After double checking, we can see that the smoking status has an empty level, we’ll clean this up before moving on

R

heart$smoking_status <- droplevels(heart$smoking_status)

summary(heart$smoking_status)

OUTPUT

formerly smoked never smoked smokes

885 1892 789 R

heart_checkpoint <- heart

Great! Now let’s tackle the typos in the gender column.

R

table(heart$gender)

OUTPUT

female Female male Male meal Other

5 2153 5 1402 0 1 We need to fix the typos that happened during data entry and the

single observation of Other will not be enough data for us

to draw any statistical conclusion so we’ll remove this row while we’re

at it.

We can use str_replace_all() as a search and replace

tool

R

table(str_replace_all(heart$gender, "female", "Female"))

OUTPUT

Female male Male Other

2158 5 1402 1 R

# str_replace_all(data, what we're search, what to replace with)

Remember that this only displays the output, it does not replace the columns in the dataset.

Before we apply it globally, we can set up a quick double check to make sure that the right values are changed.

R

# document which rows have the error "female"

wrong_entry <- which(heart$gender == "female")

wrong_entry

OUTPUT

[1] 127 271 941 1930 3021R

heart$gender[wrong_entry]

OUTPUT

[1] female female female female female

Levels: female Female male Male meal OtherR

# apply the search and replace

heart$gender <- str_replace_all(heart$gender, c("female" = "Female",

"male" = "Male",

"meal" = "Male"))

heart$gender[wrong_entry]

OUTPUT

[1] "FeMale" "FeMale" "FeMale" "FeMale" "FeMale"R

table(heart$gender)

OUTPUT

FeMale Male Other

2158 1407 1 There’s an issue with the “male” search grabbing from the “female” word!! Good thing we made a checkpoint earlier. Let’s bring this back to our main heart object - it’s a good habit to make some objects to checkpoint your work. In case you have not had this set up, you can always back track in your code and re-read in the object and re-run some earlier code to catch up.

R

heart <- heart_checkpoint

table(heart$gender)

OUTPUT

female Female male Male meal Other

5 2153 5 1402 0 1 Let’s try this again:

R

# From previous code

# add ^ (carrot) to the start of the search term to make sure it's only found at the start of the word

heart$gender <- str_replace_all(heart$gender, c("^female" = "Female",

"^male" = "Male",

"^meal" = "Male"))

heart$gender[wrong_entry]

OUTPUT

[1] "Female" "Female" "Female" "Female" "Female"R

table(heart$gender)

OUTPUT

Female Male Other

2158 1407 1 The ^ is a special character that indicates the start of

a word.

Lastly, we’ll the one Other entry

R

heart <- heart[!heart$gender == "Other", ] # object[rows, col]

table(heart$gender)

OUTPUT

Female Male

2158 1407 Overall, the data is looking much cleaner than when we started!

Exercise

Investigate the work_type column and correct the data

entry problems! Also, remove any “N/A” entries under

bmi

R

table(heart$work_type)

OUTPUT

children Govt_job Govt_job Never_worked Private

69 534 1 14 2281

Private Self-employed Self-employed

3 662 1 R

levels(heart$work_type)

OUTPUT

[1] "children" "Govt_job" "Govt_job " "Never_worked"

[5] "Private" "Private " "Self-employed" "Self-employed "R

heart$work_type <- str_replace_all(heart$work_type, c("Govt_job " = "Govt_job",

"Private " = "Private",

"Self-employed " = "Self-employed"))

class(heart$work_type)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"R

heart$work_type <- as.factor(heart$work_type)

R

summary(heart$bmi)

OUTPUT

N/A 28.4 28.7 27 27.6 25.5 27.3 26.1 26.7 26.9